OceanICU colleagues Dr. Carla Freitas and Morten Skogen, of the Institute of Marine Research (IMR) in Norway recently joined Richard Sanders, Andrew Watson and Pernille Schnoor for the first OceanICU webinar. Read on to learn about their important research!

600 tonnes of poo each day! That’s the estimate of excretion from minke whales around Svalbard, Norway

Whales and carbon

In June of 2023, an investigation for the OceanICU project kicked off when a Minke whale was tagged off the coast of Norway. The process was quick and painfree to the mammal who is now, in a manner of speaking, a silent partner in this research project.

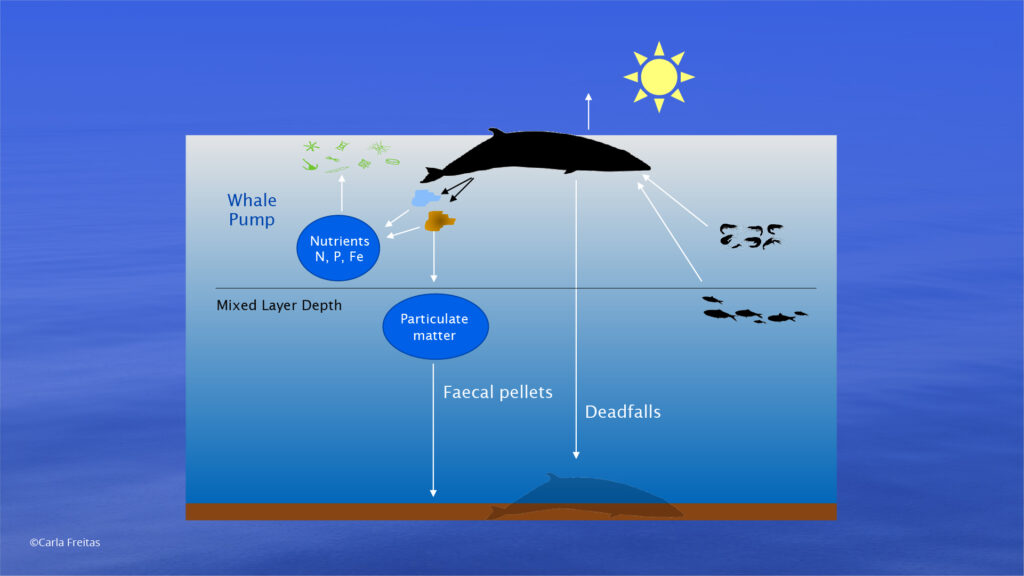

“Our aim is to increase our understanding of the oceanic carbon cycle – especially the biological carbon pump, which is more complex than previously assumed,” Dr. Carla Freitas says. Previous research has mainly focused on how phytoplankton and bacteria affect the biological carbon cycle in the ocean – how phytoplankton through photosynthesis absorb CO₂, which then becomes part of the food chain or sinks to the deep sea, where it is stored. In recent years, scientists have highlighted the need for more extensive knowledge of how organisms at higher trophic levels – such as whales – contribute.

This is exactly what the IMR-scientists are investigating now as part of OceanICU. Their primary focus is the minke whale, as there is already good biological data for this species in the study area. How do whales contribute to the biological carbon cycle?

They are the Ocean’s sheep

When whales eat – either at the surface or at depth – they excrete a large amount of feces and urine. In total, minke whales around Svalbard, Norway have been estimated to excrete 600 tons of poo each day. Scientists have a hypothesis that whale poo and urine are important for phytoplankton – that the poo fertilizes the ocean, similarly to how poo from cows and sheep fertilize land. “We are estimating the amount of nutrients whales excrete, as currently there is a lack of good data,” Freitas says. The whale tags will aid scientists to find out where whales acquire nutrients – how deep they dive, and where in the water column they eat.

“The next step is to investigate how phytoplankton absorbs the nutrients,” explains scientist Kjell Gundersen, a colleague of Freitas, and the principal investigator in the phytoplankton experiments. “In addition, we’ll investigate how much carbon sinks to the deep sea – both through whale excretions and when whales die and their bodies sink to the seabed,” Freitas adds.

Interesting route

Already, the first minke whale tagged outside Andenes in Norway has given useful information. Every time the whale surfaces, the tag sends data to scientists via satellite. “The minke whale travelled fast northwards, and after a couple of days, it reached the northernmost parts of Russia,” Freitas says.

The tagged whale was most likely migrating to its summer feeding grounds in the Nordic Seas. During winter, minke whales use warmer waters, where they mate and give birth. The tag is programmed to collect a large amount of data on location and diving behaviour during the first days; the tag will then fall on its own with no harm to the whale. During the summer, two additional whales were tagged – and researchers hope to tag more whales.

New sources for updated models

The new data from the tags and from lab analysis, will end up in the hands of marine scientist Morten Skogen, who works with ecosystem models. He is part of the OceanICU project work group responsible for further developing our current models with the new knowledge gained from the results of the whale tagging research.

“Our main goal is to investigate carbon cycling. To reduce uncertainties in climate forecasts, it is crucial to include all the most important processes,” Skogen says. Global models, regional models and process models will all be examined. Scientists will explore how the models can be improved, and how to better transfer knowledge from local processes to the global carbon budget – to improve our understanding of what role each part plays in the oceanic carbon cycle. When Carla Freitas has collected data on where minke whales travel and where they eat, Skogen will include this data as a source for the very first time. Then he’ll run the same model twice: once with the whale data, and once without – to see how important the poo is. “There are whales in all oceans, so the big question is how much they contribute to carbon cycling globally,” Skogen says.

Stay tuned to OceanICU for the results of this study and many other components of research being conducted to help scientists, industry and policymakers improve our understanding of the Ocean carbon cycle. Subscribe to the newsletter!

For more on this whale study, please see:

Minke whales around Svalbard excrete 600 tonnes of poo each day (article) – READ MORE

Dr. Carla Freitas

Dr. Carla Freitas is a senior scientist at the Institute of Marine Research in Norway. Her main research interests are spatial ecology of marine top predators, including marine mammals, sea turtles and predatory fish. Using animal telemetry, she studies how these species use their environment, as well as their ecological role in marine ecosystems – including their impact on the ocean carbon cycle.

Dr. Morten D. Skogen

Dr. Morten D. Skogen is a research professor at the Institute of Marine Research in Bergen, Norway. He has been working more than 30 years with ecosystem models, and has the main responsibility for development and maintenance of the ecosystem model NORWECOM.E2E. His main research interests are on Individual Based Models, climate-fish interactions, eutrophication and ocean acidification.